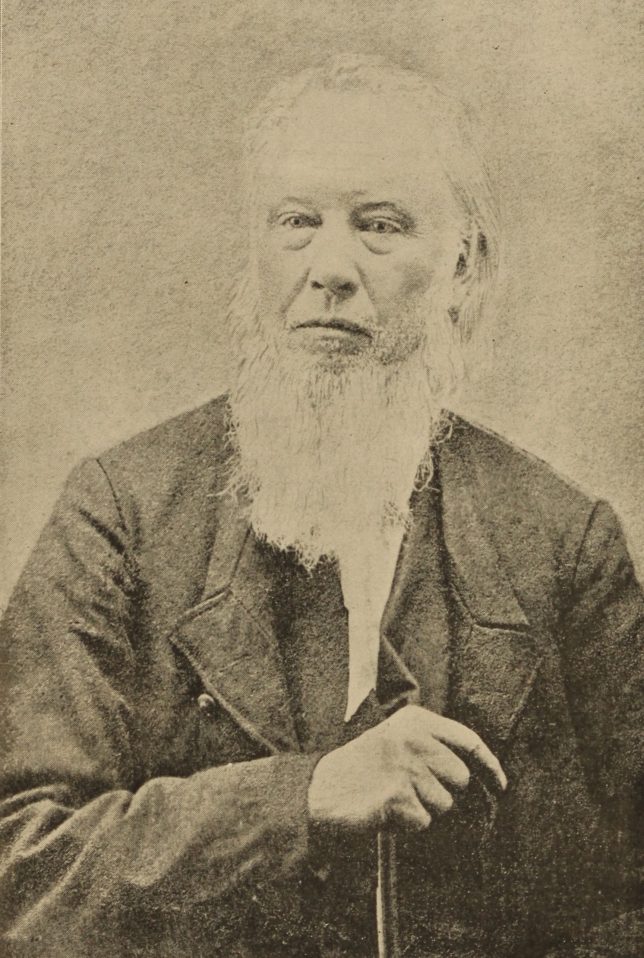

American slavery had been a hot topic for many years, and tempers flared whenever it came up. What is a Christian to do in such cases? Should he (like Isaac Errett) pretend the problem doesn’t exist? Or should he (like Pardee Butler) stand up and fight against it?

This week’s Restoration Moment comes from “The Personal Recollections of Pardee Butler,” which appears in Pardee Butler: The Definitive Collection. These are Pardee Butler’s own words:

The things that had been happening in the Kansas Territory [regarding slavery] had been so strange and unheard of, and the threats of the Squatter Sovereign had been so savage and barbarous, that I wanted to carry back to my friends in Illinois some evidence of what was going on. I went, therefore, with Bro. Elliott to the Squatter Sovereign printing office to purchase extra copies of that paper. I was waited on by Robert S. Kelley. After paying for my papers I said to him: “I should have become a subscriber to your paper some time ago only there is one thing I do not like about it.” Mr. Kelley did not know me, and asked: “What is it?”

I replied: “I do not like the spirit of violence that characterizes it.”

He said: “I consider all Free-soilers rogues, and they are to be treated as such.”

I looked him for a moment steadily in the face, and then said to him: “Well, sir, I am a Free-soiler; and I intend to vote for Kansas to be a Free State.”

He fiercely replied: “You will not be allowed to vote.”

When Bro. Elliott and myself had left the house, and were in the open air, he clutched me nervously by the arm and said: “Bro. Butler! Bro. Butler! You must not do such things; they will kill you!”

I replied: “If they do I cannot help it.”

Bro. Elliott was now to go home. But before going he besought me with earnest entreaty not to bring down on my own head the vengeance of these men. I thanked him for his regard for me, and we bade each other goodbye.

Bro. Elliot had come to feel that my life was precious to the Christian brethren in Atchison county. Except myself they had no preacher. And they needed a preacher.

The steamboat bound for St. Louis that day had been detained, and would not arrive until the next day. I must, therefore, stay overnight in Atchison. I conversed freely with the people that afternoon, and said to them: “Under the Kansas-Nebraska bill, we that are Free State men have as good a right to come to Kansas as you have; and we have as good a right to speak our sentiments as you have.”

A public meeting was called that night to consider my case, but I did not know it. The steamboat was expected about noon the next day. I had been sitting writing letters at the head of the stairs, in the chamber of the boarding-house where I had slept, and heard someone call my name, and rose up to go down stairs; but was met by six men, bristling with revolvers and bowie-knives, who came upstairs and into my room. The leader was Robert S. Kelley. They presented me a string of resolutions, denouncing Free State men in unmeasured terms, and demanded that I should sign them. I felt my heart flutter, and knew if I should undertake to speak my voice would tremble, and determined to gain time.

Sitting down I pretended to read the resolutions—they were familiar to me, having been already printed in the Squatter Sovereign—and finally I began to read them aloud. But these men were impatient, and said: “We just want to know will you sign these resolutions?” I had taken my seat by a window, and looking out and down into the street, had seen a great crowd assembled, and determined to get among them. Whatever should be done would better be done in the presence of witnesses. I said not a word, but going to the head of the stairs, where was my writing-stand and pen and ink, I laid the paper down and quickly walked down stairs and into the street. Here they caught me by the wrists, from behind, and demanded, “Will you sign?”

I answered, “No,” with emphasis. I had got my voice by that time. They dragged me down to the Missouri River, cursing me, and telling me they were going to drown me. But when we had got to the river they seemed to have got to the end of their programme, and there we stood. Then some little boys, anxious to see the fun go on, told me to get on a large cotton-wood stump close by and defend myself. I told the little fellows I did not know what I was accused of yet. This broke the silence, and the men that had me in charge asked:

“Did the Emigrant Aid Society send you here?”

“No; I have no connection with the Emigrant Aid Society.”

“Well, what did you come for?”

“I came because I had a mind to come. What did you come for?”

“Did you come to make Kansas a Free State?”

“No, not primarily; but I shall vote to make Kansas a Free State.”

“Are you a correspondent of the New York Tribune?”

“No; I have not written a line to the Tribune since I came to Kansas.”

By this time a great crowd had gathered around, and each man took his turn in cross-questioning me, while I replied, as best I could, to this storm of questions, accusations and invectives. We went over the whole ground. We debated every issue that had been debated in Congress. They alleged the joint ownership the South had with the North in the common Territories of the nation; that slaves are property, and that they had a natural and inalienable right to take their property into any part of the national Territory, and there to protect it by the strong right arm of power. While I urged the terms of the Kansas-Nebraska bill, and that under it Free State men have a right to come into the Territory, and by their votes to make it a Free State, if their votes will make it so.

At length an old man came near to me, and dropping his voice to a half-whisper, said in a confidential tone: “Nee-ow, Mr. Butler, I want to advise you as a friend, and for your own good, when you get away, just keep away.”

I knew this man was a Yankee, for I am a Yankee myself. His name was Ira Norris. He had been given an office in Platte County, Mo., and must needs be a partisan for the peculiar institution. I gave my friend Norris to understand that I would try to attend to my own business.

Others sought to persuade me to promise to leave the country and not come back. Then when no good result seemed to come from our talk, I said to them: “Gentlemen, there is no use in keeping up this debate any longer; if I live anywhere, I shall live in Kansas. Now do your duty as you understand it, and I will do mine as I understand it. I ask no favors of you.”

Then the leaders of this business went away by themselves and held a consultation. Of course I did not know what passed among them, but Dr. Stringfellow many years afterwards made the following statement to a gentleman who was getting up a history of Kansas:

“A vote was taken upon the mode of punishment which ought to be accorded to him, and to this day it is probably known but to few persons that a decided verdict of death by hanging was rendered; and furthermore, that Mr. Kelley, the teller, by making false returns to the excited mob, saved Mr. Butler’s life. … At the time the pro-slavery party decided to send Mr. Butler down the Missouri River on a raft…”

The crowd had now to be pacified and won over to an arrangement that should give me a chance for my life. A Mr. Peebles, a dentist from Lexington, Mo., … a slave-holder, was put forward to do this work. He said: “My friends, we must not hang this man; he is not an Abolitionist, he is what they call a Free-soiler. The Abolitionists steal our niggers, but the Free-soilers do not do this. They intend to make Kansas a Free State by legal methods. But in the outcome of the business, there is not the value of a picayune of difference between a Free-soiler and an Abolitionist; for if the Free-soilers succeed in making Kansas a Free State, and thus surround Missouri with a cordon of Free States, our slaves in Missouri will not be worth a dime apiece. Still we must not hang this man; and I propose that we make a raft and send him down the river as an example.”

And so to him they all agreed. Then the question came up, What kind of a raft shall it be? Some said, “One log”; but the crowd decided it should be two logs fastened together. When the raft was completed I was ordered to take my place on it, after they had painted the letter R. on my forehead with black paint. This letter stood for Rogue. I had in my pocket a purse of gold, which I proffered to a merchant of the place, an upright business man, with the request that he would send it to my wife; but he declined to take it. He afterwards explained to me that he himself was afraid of the mob. They took a skiff and towed the raft out into the middle of the Missouri River. As we swung away from the bank, I rose up and said: “Gentlemen, if I am drowned I forgive you; but I have this to say to you: If you are not ashamed of your part in this transaction, I am not ashamed of mine. Goodbye.”

—

Pardee Butler survived his “rafting,” and later returned to town where he was “tarred and cottoned” (they had no feathers to use). But still he kept returning, and kept fighting against slavery until the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Lincoln.